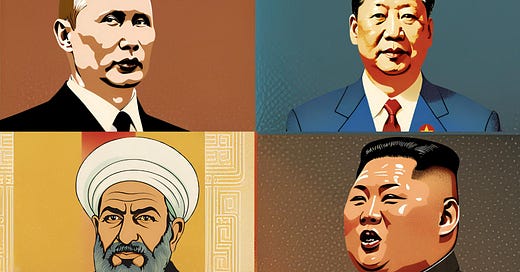

There is increasing evidence that the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Russia, Iran and North Korea – brought together under the new acronym, the CRINK – are forming closer relations and working together to oppose the open international order. These revisionist powers pose a significant challenge to the United Kingdom (UK) and its allies and partners, not just militarily but also across other key sectors, including economics, manufacturing, science and technology. So, in this week’s Big Ask, we asked eight experts: Is the CRINK a geostrategic threat?

Neil Brown

Distinguished Fellow, Council on Geostrategy

North Korea’s deployment of troops to Russia confirms what has been clear for some time. Diplomatically, economically, and militarily, the CRINK is connected and active in a way that poses a threat to the open international order. Their support to Russia’s military and military-industrial complex for its war of aggression against Ukraine, and what Russia is providing in return, sees two permanent members of the United Nations (UN) Security Council and two of the world’s most UN-sanctioned states combining to increase global military risk and undermine the functioning of the Security Council.

But these nations are not natural bedfellows. Deep suspicions, present in PRC-Russian and PRC-Korean relations – even when they were fellow Communist powers – remain, but importantly, they have a common cause. However, unlike their predecessors, this ‘deadly quartet’ includes the world’s second largest economy and largest trading nation, and two of the world’s largest fossil fuel producers, which gives them collective resilience and influence that they wield strategically across global energy, commodities and currency markets while also developing advanced technologies and control over vital supply chains.

The CRINK are a threat not only because of their ability to bully, but their ability (individually and collectively and amplified by an enlarged BRICS) to attract politically and economically weakened democracies and the so called ‘middle ground’ countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The combined reach of the CRINK nations manifests itself in comprehensive threats across the Euro-Atlantic and the Indo-Pacific; countering it will demand a similarly comprehensive response.

Director, Mayak Intelligence

The CRINK, much like the BRICS, is at once a real thing – and a strategic trap of our own making. A snappy acronym or dramatic term (such as ‘axis of evil’ or, indeed, ‘deadly quartet’) may be useful for drawing attention to a rising challenge, but often conveys a false sense of unity and common purpose.

There is no doubt that rising powers such as the PRC, disgruntled revanchists such as Russia, and angry pariahs such as Iran and North Korea have good, practical reasons to cooperate in bypassing sanctions. Allowing them to trade everything from ammunition to technical know-how, and challenge what they regard – not wholly without reason – as a global order created by the United States (US) and its allies to protect their own interest. In this, as we see with the willingness of so many countries to cooperate in sanctions busting, or the expansion of BRICS, or the hunger for Chinese investment, they are by no means alone.

However, there are serious and enduring differences in goals and means. The PRC does not want to see the Kremlin defeated in Ukraine, but nor is it willing to court secondary sanctions for Russia, just as Moscow is desperately hoping it is never forced to choose between active participation in a Chinese war against Taiwan – and thus facing a US-led coalition – and losing its support. North Korea and Iran will arm Russia, yet for pay, not fellowship. These are limited and fair-weather friends. While they all pose their own geostrategic threats to the democratic world, if we convince ourselves that they are a single, coherent one, we misunderstand the nature of the challenge and make it more formidable than it really is.

Senior Director of Policy, China Strategic Risks Institute

Without the tacit consent and the active participation of officials in Beijing, it is hard to see how such a grouping of Russia, North Korea, Iran and the PRC, would turn a set of transactional and pragmatic arrangements between these authoritarian regimes into a more formal military or economic alliance which could pose a geostrategic threat.

The success of such a grouping, if it were to emerge, would depend heavily on the geopolitical weight and financing of the PRC. Beijing’s participation would guarantee global bifurcation through the eventual development of alternative international payment systems, the ability for these regimes to bypass sanctions, and a potential fulfilment of the aspiration of breaking the liberal democratic world’s chokehold on the global financial system.

The PRC’s civil-military fusion programme and the resources it has invested into emerging technologies could be used to upgrade and modernise the respective militaries of the CRINK nations, which might close the military gap and shift the balance of power in the medium term from West to East.

Of course, the PRC has far more reasons to be wary of such an alliance than the other members. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), for now, still favours a cordial relationship with Euro-Atlantic countries and needs their consumers to buy its goods and foreign investors to prop up its struggling economy.

Lecturer in International Relations, University of Oxford, and Korea Foundation Fellow, Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House)

If there is one thing that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has taught us, it is that in an interconnected world, conflict in Europe is not limited to Europe. North Korea is now a full-fledged participant in – and not a mere observer of – Russia’s war against Ukraine, assisting Moscow not just by supplying millions of shells, but ballistic missiles and, as has been most recently announced, approximately 1,500 troops so far. Pyongyang is also supplying weapons to terrorist actors, not least Hamas (via Iran), escalating the concerning potential for expanded horizontal weapons proliferation. While the PRC has remained largely silent about the rapprochement between Moscow and Pyongyang, Beijing continues to assist North Korea in its evasion of sanctions, and to trade in dual-use technologies with Russia.

What makes the CRINK a geostrategic threat is the fact that, while the individual interests of the four states are far from identical, they are firmly united in their desire to revise the status quo. All four countries seek to forge a united front in resisting open international order and the values of the democratic world, and, instead, repeatedly call for an ‘alternative global order’. With North Korea having gained Russia’s unwavering support at the toothless UN Security Council – rendering the already impotent council even more so – a key concern relates to how the international community can deal with, and monitor, the actions of rogue states.

Assistant Professor in Politics and International Relations, University of Nottingham

As with most (formal and informal) alliances, the CRINK is a partnership of convenience, where not all interests align. Iran and North Korea, for example, have a shared experience of heavy sanctions, pursuing nuclear weapons and priding themselves on independence and developing homegrown military industries. But North Korea is not a religious country – despite allowing the Iranian Embassy to open a Shia mosque – and differs from Iran in its views on the Taliban and the Islamic State.

Similarly, while the PRC has been Iran’s biggest trading partner for the past decade, and Beijing has helped to rehabilitate Tehran diplomatically (for example through supporting Iran’s membership into the Shanghai Cooperation Operation and the expansion of BRICS), relations have also been strained over the lack of Chinese investment in Iran and previous attempts to influence policy over the Houthis in Yemen.

Consequently, the CRINK relationship is transactional, with different cultures, leadership structures, power dynamics, values and approaches. However, while not united in support of a common cause or ideology, the CRINK members are united by a shared opposition to the US, its allies and the current international order. Each has their own approach to undermining this order – around issues of security, economics, manufacturing, science and technology – but collectively the seams holding the current status quo together are rapidly being undone. Countering this process will require a multidimensional approach to each threat, a re-evaluation of relations with each country and exploitation of the weaknesses in between the CRINK states themselves.

Dr Ksenia Kirkham

Lecturer in Economic Warfare, King’s College London

With hostile rhetoric, a potential threat has the tendency to become a real one. Iran, North Korea and Russia have long been dubbed the ‘axis of evil’, pariah nations outside the US-led security architecture. Yet, accusations and sanctions have not made them less powerful, nor more friendly. Quite the opposite. For Beijing, the stakes are even higher – labelling the PRC a ‘threat’ and an ‘epoch-defining challenge’ in the Integrated Review Refresh (in place of the previous ‘systemic challenge’) could be a grave strategic mistake. The appearance of many ‘CRINKs’ is the evidence.

This acronym, however, is an optimistic oversimplification, as the real number of ‘revisionist’ powers is much higher. The BRICS+ Summit held in Kazan, Russia, this week is a symbolic reflection of tectonic shifts in the global political economy. Most attendees agree with India’s stance that BRICS+ is not ‘anti-western’, but just a ‘non-western group’, as well as with Brazil’s call for a multipolar global financial system.

Neither sanctions nor export controls will effectively disrupt the growing economic, scientific and military synergies of these emerging economies in the long run. Beijing’s powerful economy cannot be ‘contained’ and a total decoupling from the PRC is not realistic.

The CRINK nations pose a strategic challenge to the current status quo. With most mechanisms of deterrence failing to stop them, while simultaneously pushing certain non-aligned nations closer to the bloc, a change of strategy is required. To avoid further escalation, it would be naïve not to remember the wisdom ‘if you can’t defeat your enemy, make him your friend’. This could invite mirror actions from the CRINKs.

Member of the Advisory Board, China Observatory and Research Associate, University of Oxford’s China Centre

The CRINK countries are not so much an alliance of like-minded nations bound together by shared values and beliefs, as a PRC-centric constellation of autocratic countries, including two hydrocarbon states and one state with no commercial significance, with only one thing in common: to oppose the US, undermine its global leadership, and reframe the international system to better suit their political interests.

It is tempting but probably unwise for democratic policymakers to think that, despite the ambition of the CRINKs, they comprise a loose association of countries with various and sometimes incompatible interests, structured into a Beijing-dominated vehicle, such as the BRICS or the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The PRC accounts for four-fifths or more of the group’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and population, but unlike the other Chinese vehicles for influence, which have goals related to alternative economic, infrastructure, and financial policy structures and arrangements, the CRINK countries have a much more military, intelligence, cyber, and logistics-related raison d’être that could also cause economic turbulence.

Beijing’s support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and recent reports of Iranian military hardware and North Korean troops being sent to Russia suggest that this quirky quartet should, notwithstanding its features, figure prominently in British and allied foreign policy thinking and planning.

Former Head of the UK’s Global Strategic Trends programme, Senior Adjunct Fellow, Pacific Forum and Senior Advisor, Herminius Strategic Intelligence

In many ways, the CRINK is an oversimplification of complex, and not always harmonious, relationships between the four nations. It is, however, a useful rallying cry for democratic countries to do more, more urgently, given the increasing boldness and alignment being demonstrated by these countries as they seek to rewrite the international system.

Most immediate is Iran’s transition from proxy war to direct attacks on Israel, with the world holding its breath regarding the next step. Equally pressing, however, is support the others are giving Russia. Iran and North Korea have rapidly moved from diplomatic posturing to directly supplying weapons, while Pyongyang appears to be deploying troops on European soil. The PRC is buying up Russian oil and abetting its defence manufacturers in ways intended to circumvent international sanctions.

Battlefield events are increasingly aiding the PRC and Russia’s hold on the attention of ‘middle ground’ nations, building on the economic and diplomatic reach of the BRI and BRICS+. All of which could shape the geostrategic ground ahead of yet further – and potentially worse – crises on the Korean peninsula or across the Taiwan Strait, in which the other CRINKs could play both direct and distracting roles.

Yet the ‘crink’ in the CRINK is the absence of genuine partnership beyond an alignment of interests. Beijing, Moscow and Tehran all compete in Central Asia, while the PRC is far from comfortable with Russia and North Korea’s new defence pact. Meanwhile, Beijing is exploiting Moscow’s weakness to grow its posture in the Russian Far East, territories it has coveted since losing them during the so-called ‘Century of Humiliation’.

Alongside re-investment in military capacity and protection from economic coercion, these are all vulnerabilities which democratic partners should be more actively exploiting to help break the CRINK’s current momentum.

Read more: Rise of the CRINK? – James Rogers 24/10/2024

If you enjoyed this Big Ask, please subscribe or pledge your support!

What do you think about the perspectives put forward in this Big Ask? Why not leave a comment below?

A thoughtful article. Thank you.